|

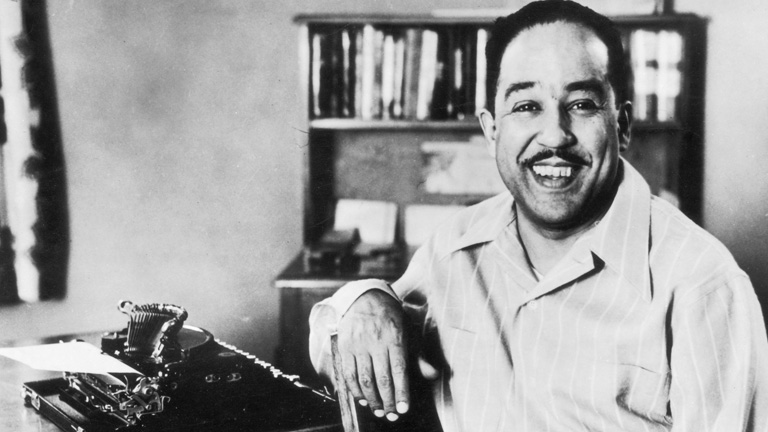

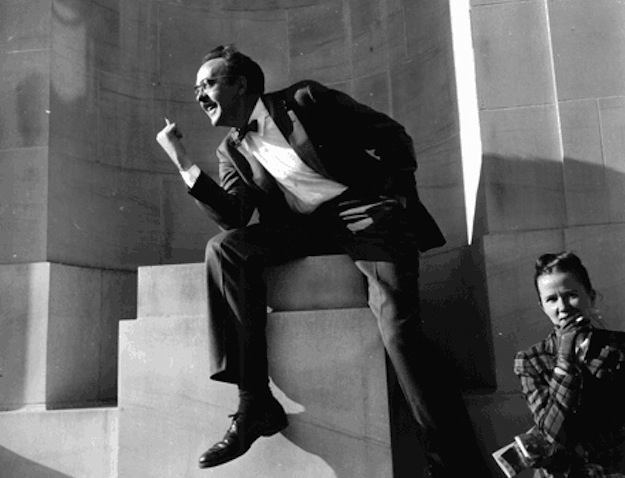

| (left to right): Thomas Sayers Ellis, Fred Moten, A.L. Nielsen, Kevin Young |

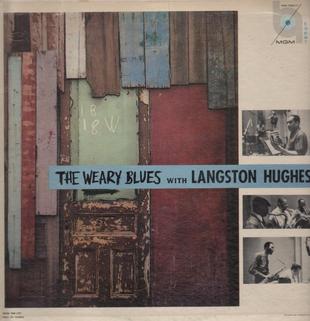

On Friday, we'll look at we'll look at a quartet of contemporary poets working within the shadows of Hughes, Baraka, and the Beats while also transforming the sounds and syntax of more modern musical forms: Thomas Sayers Ellis, Fred Moten, A.L. Nielsen, and Kevin Young.

Our selections from Thomas Sayers Ellis come from his wonderful first collection, The Maverick Room (Graywolf, 2005), and will include the complete title suite. We'll read a handful of pieces by Fred Moten, taken from two of his earlier books, Hughson's Tavern (leon works, 2008) and B. Jenkins (Duke University, 2010). You'll find several full-length readings by Moten on his PennSound author page, including segmented tracks for many of the poems we'll read for today, and if you're interested in further reading, check out 2014's The Feel Trio, which was a finalist for the National Book Award this year. The source of our readings from A.L. Nielsen is his latest collection, A Brand New Beggar (Steerage Press, 2013), and you can hear him reading his work on his PennSound author page (though sadly no tracks are available for our selections). Finally, we'll read some pieces from the original version of Kevin Young's To Repel Ghosts, a book inspired by the work of maverick painter Jean-Michel Basquiat (Zoland Books, 2002), which reappeared in a remixed version published by Knopf in 2005.

- A Pack of Cigarettes

- Sticks

- The Maverick Room (complete sequence)

Fred Moten (Hughson's Tavern marked "HT," all others from B. Jenkins): [PDF]

- jazz (as ken burns (HT) [MP3]

- trumpeters (HT)

- bebop (HT)

- billie holiday/roland barthes

- fishbone/joseph jarman [MP3]

- elvin jones, malachi favors, steve lacy [MP3]

- yopie prins

- sherrie tucker, francis ponge, sun ra [MP3]

- william parker/fred mcdowell [MP3]

- cecil taylor/almeida ragland [MP3]

- charlie parker