While most of you posted your final podcasts to our Facebook group I thought I'd create a playlist here on our blog as well. Note that a number of students attached their podcasts to their e-mails and didn't put them up on SoundCloud, so their tracks are missing here (but feel free to upload them, drop me a line, and I'll add them). It's been a great semester and I can't believe our time is over. I hope you have a wonderful summer!

Monday, May 4, 2015

Tuesday, April 14, 2015

Wednesday, April 22 — Homophonic / Homolinguistic Translation, Mondegreens, etc.

We're closing the term out in somewhat irreverent fashion, but while our readings for today might seem more like fun and games, there are serious aesthetic notions at work beneath the humorous surface.

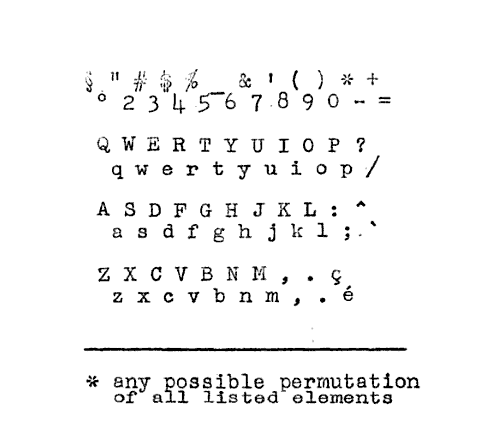

First, we'll take a look at homophonic and homolinguistic translations. While the two terms are frequently used interchangeably, if we're getting technical homophonic translation describes transformative processes in which a text is translated from a foreign language into English — as Charles Bernstein explains on his infamous experiments list, "Take a poem in a foreign language that you can pronounce but not necessarily understand and translate the sound of the poem into English (e.g., French "blanc" to blank or "toute" to toot)" — whereas homolinguistic translation describes similar translations of "English into English."

You've already encountered a few examples, including Kenneth Koch's "Transposed Hamlet" ("Tube heat, or nog tube heat . . ."), Ted Berrigan's "Mess Occupations," and Christian Bök's transformation of Arthur Rimbaud's "Voyelles" as "Veils" in our last class, and I thought we'd take a look at a few more examples for today.

You've already encountered a few examples, including Kenneth Koch's "Transposed Hamlet" ("Tube heat, or nog tube heat . . ."), Ted Berrigan's "Mess Occupations," and Christian Bök's transformation of Arthur Rimbaud's "Voyelles" as "Veils" in our last class, and I thought we'd take a look at a few more examples for today.

First, here's Kenneth Goldsmith's "Head Citations" [read / listen], which elevates misheard song lyrics to found poetry. Then check out Bernstein's "From the Basque" [link], and Ron Silliman's discussion of the technique [link], which includes examples from Chris Tysh, David Melnick, and his own writing. You can find more examples on the Wikipedia page for homophonic translation, and those interested in far deeper (albeit optional) reading in the form should look at Six Fillious, an ambitious multilingual collaboration between six authors (including George Brecht), which was published in 1978.

This is an avant-garde technique that gets used a hell of a lot more commonly than you might imagine. For example:

or

A few more interesting examples include Italian songwriter Adriano Celentano's 1972 gibberish song "Prisecolinensinenciousol," which is intended to sound like American English:

And a more recent example in the same vein as Celentano's experiment is Skwerl, a short film by Karl Eccleston and Brian Fairbairn, which aims to capture how English sounds to non-English speakers:

If you find this technique interesting, you might also want to check out the related phenomena of Mondegreens and Anguish Language, and in a certain regard, I think this is the most beautifully commonplace poetry, since it infiltrates our everyday lives far more successfully than what we typically think of as poetry. Towards that end, it feels like a very appropriate way in which to end the semester.

Monday, April 20 — Sound and Subversion 3: Outside the US

|

| Caroline Bergvall in performance, 2014. |

First, Caroline Bergvall, whose peripatetic lifestyle — born in Germany to French and Norwegian parents, Bergvall has lived in Geneva, Paris, Oslo, and New York before settling in London — plays an important role in the development of her poetics. Language is first and foremost a constructed thing, and a living construct at that, ripe for deconstruction, contradiction, reconfiguration and rediscovery. Specifically, in Bergvall's hands, the English language is a most malleable medium, which is brought into contact with its own roots (both Middle English and the Latinate and Germanic tongues that helped shape it), yielding spectacular results in her "Shorter Chaucer Tales," which reintent the Canterbury Tales in modern ways. One other idea to bear in mind is Bergvall's multidisciplinary approach to poetry. She bills herself as both a poet and a text-based artist, and the spirit of live performance, as well as a responsiveness to texts of various media (cf. "Untitled" and "Fuses," which respond to song and film, respectively) permeate her writings: [PDF]

- The Host Tale [MP3]

- The Summer Tale (Deus Hic 1) [MP3]

- The Franker Tale (Deus Hic 2) [MP3]

- Untitled (Roberta Flack can clean your soul — out!) [MP3]

- Fuses (after Carolee Schneemann) [MP3]

- Doll (starts in PDF after "Fuses" on pg. 71, recording doesn't exactly match text) [MP3]

Next, we'll look at a few pieces by Dutch modern-day avant-garde troubadour, Jaap Blonk, whose aesthetic journey began as a free-jazz saxophonist and evolved into musical/textual performances involving electronics before he came to a performance style focused solely on the voice, and his voice is an astounding instrument, fully matching his imposing six-and-a-half foot frame. We'll look at three pieces by Blonk, along with a few performances of others work.

- Let's Go Out (text with audio, another recording here [MP3])

- Sound (text with audio)

- What the President Will Say and Do [MP3]

|

| A detail from Martín Gubbins' "White Pages." |

Finally, because of the overlap between concrete poetry and sound poetry, I thought it might be fun to take a look at "Antología Poesía Visual," a marvelous anthology of Chilean visual poetry curated by Nico Vassilakis for Jacket2 in 2014, which contains work by Anamaría Briede, Gregorio Fontén, Kurt Folch, Martín Barkero, and Martín Gubbins.

Friday, April 10, 2015

Friday, April 17 — Sound and Subversion 2: North America

|

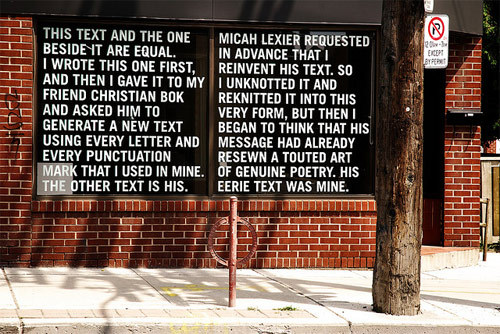

| Christian Bök's "Two Equal Texts," on-site installation. |

First up is Christian Bök, who's perhaps best known for his book-length Oulipian experiment, Eunoia, a lipogramatic text, that is one in which some sort of linguistic restriction guides its composition: specifically, each of the five chapters, named for one of the vowels, only contains words containing those vowels. In addition, Bök has instituted several other rules, including making use of at least 98% of all existing words featuring the given vowel, as well as specific tasks, including writing about the act of writing, a feast, a debauch, a nautical journey, etc. You might recall Stefans talking about the text in relation to his setting of the E chapter in last Friday's readings.

We'll look at two chapters in their entirety, and then a few selections from the companion "Oiseau" section, including several variations on Arthur Rimbaud's "Voyelles," which synesthetically ascribes colors to each of the vowels. [PDF] Recordings from Bök's PennSound author page are linked when available.

- Eunoia, chapter A [MP3]

- Eunoia, chapter O [MP3]

- Voyelles [MP3]

- Vowels [MP3]

- Phonemes [MP3]

- Veils

- Vocables [MP3]

- AEIOU

- And Sometimes [MP3]

- Vowels [MP3]

- H (for bpNichol)

- Voile [MP3]

Next, we have bpNichol, shown above with his poem, "The Complete Works." We'll take a look at some selections from The Alphabet Game: a bpNichol Reader, which highlight some of nichol's more purely sonic experimentations, however he worked in a wide variety of media, starting as a concrete poet (a genre that often indirectly features some sort of sonic subterfuge), but moving on to work in collages, musical theatre, television (among other jobs, he wrote scripts and songs for Fraggle Rock) and even very early experiments in computer poetry with First Screening: Computer Poems (1983–84) for the Apple IIe (you can watch an emulated version here). Sadly, nichol died at the very young age of 43 after complications from surgery on his back but his work and influence carry on, most notably in bpNichol Lane (see below) in Toronto, where, at #80, you can find Coach House Press, one of Canada's longest and most-acclaimed publishers of experimental poetry. nichol's PennSound author page can be found here, and your readings are here: [PDF]

In addition to his own writing, nichol founded The Four Horsemen with poets Steve McCaffery, Paul Dutton, and Rafael Barreto-Rivera. This group, which took the ideas of concrete and sound poetry into fascinating — if sometimes perplexing — live performances that combined high-minded literary conceptualism with the raucous energy of a rock show. You can see their performance from Ron Mann's film, Poetry in Motion below, and find a wide variety of recordings on their PennSound author page. For an optional, yet highly-intriguing sonic experience, you might also want to check out Paul Dutton's "so'nets."

Finally, we'll look a a suite of poems published in Poetry Magazine in a special 2009 issue devoted to Flarf and Conceptual poetry which was edited by Kenneth Goldsmith. In his introduction, he makes some (understandably) controversial statements that nonetheless aptly give a sense of the state of contemporary cutting-edge poetic practice:

Start making sense. Disjunction is dead. The fragment, which ruled poetry for the past one hundred years, has left the building. Subjectivity, emotion, the body, and desire, as expressed in whole units of plain English with normative syntax, has returned. But not in ways you would imagine. This new poetry wears its sincerity on its sleeve . . . yet no one means a word of it. Come to think of it, no one’s really written a word of it. It’s been grabbed, cut, pasted, processed, machined, honed, flattened, repurposed, regurgitated, and reframed from the great mass of free-floating language out there just begging to be turned into poetry. Why atomize, shatter, and splay language into nonsensical shards when you can hoard, store, mold, squeeze, shovel, soil, scrub, package, and cram the stuff into towers of words and castles of language with a stroke of the keyboard? And what fun to wreck it: knock it down, hit delete, and start all over again. There’s a sense of gluttony, of joy, and of fun. Like kids at a touch table, we’re delighted to feel language again, to roll in it, to get our hands dirty. With so much available language, does anyone really need to write more? Instead, let’s just process what exists. Language as matter; language as material. How much did you say that paragraph weighed?

As no better (and more appropriate) a source than the Wikipedia page on Flarf observes, "Its first practitioners, working in loose collaboration on an email listserv, used an approach that rejected conventional standards of quality and explored subject matter and tonality not typically considered appropriate for poetry. One of their central methods, invented by Drew Gardner, was to mine the Internet with odd search terms then distill the results into often hilarious and sometimes disturbing poems, plays and other texts."

In particular, I'd like you to take a look at the contributions — which can be found here — from Jordan Davis, Sharon Mesmer, K. Silem Mohammad, Drew Gardner, Nada Gordon, and Gary Sullivan. Aside from Bök, you'll also note the issue contains work by Caroline Bergvall, who we'll be reading next week.

Wednesday, April 8, 2015

Bonus: Kit Robinson and Dolch Sight Words

This is completely independent of the readings we're doing at this point in the semester, but something I just stumbled upon, found interesting, and thought I'd share, both as a fascinating text that fits perfectly within our work this term, and to document the way in which associatively chasing ideas down the rabbit hole can yield interesting results.

I was just spending some time thinking about how I might organize my Backgrounds for English Studies course next fall — which a few of you are signed up for — and as part of that process, I looked up a list of the most common words in the English language (thanks, Wikipedia!). One of the related links at the bottom was for the Dolch word list (a list of important yet challenging words necessary for children to learn to become fluent English speakers) and that strange eponym got me thinking about Kit Robinson's poetic sequence, "The Dolch Stanzas," which I last read several years back. Harboring the suspicion that Robinson's poems, which feature very basic and straightforward language, might be composed from the Dolch list I did a little research and found this statement, from a blog post about poetry and labor:

The question of the employment of the poet has interested me almost from the beginning. My "Taxicab Diaries," from the summer of 1971 in Boston, was the first thing I had published in Barrett Watten's This magazine. My serial poem "The Dolch Stanzas" was written in 1974 while I was working as a paraprofessional teacher's aide at a San Francisco elementary school. Like work of mine to come, "Dolch" made use of the material of the workplace, in this case the Dolch Basic Sight Word List.

What makes this particular interesting for our class is the nature of many of the words on the list, as this page notes: "Many of the 220 words in the Dolch list, can not be 'sounded out,' and hence must be learned by sight." Thus the phonemic character of these words comes via memorization, rather than any visual cues.

If you'd like to read Robinson's brief sequence, you can find it here; a 1990 reading of the series can be found here: [MP3]

Bonus Fun Fact: Kit Robinson and I share the same birthday (May 17), which is a popular birthday for poets, also being shared by Lyn Hejinian and Sara Wintz. Go Taureans!

Monday, April 6, 2015

Wednesday, April 15 — Dada Poetics and the Indecipherable

|

| (l) Hugo Ball performs "Karawane" at the Cabaret Voltaire in "a cubist costume" (r) Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven strikes a provocative pose. |

As the end of the semester nears, we're coming full-circle, returning to the Dadaist poetics of Tristan Tzara and his peers, however whereas before we simply considered his instructions for creating Dada poetry as a precursor of Burroughs and Gysin's cut-up techniques, today we'll actually take a look at the work he created through those methods.

A potent international multimedia movement with roots in Zurich's Cabaret Voltaire, Dadaism emerged in reaction to the horrors of the First World War. While its aesthetic far too often gets reduced to formulas like "the world didn't make sense so their art didn't make sense," there are far more complex ideological underpinnings that took issue with nationalism and colonialism, bourgeois politics and aesthetics, and the destructive potential of modern industrialism. That having been said, Dadist ideology was largely centered on shock value and the opportunity for critical rethinking that came with it. One key way they achieved this was through the use of unconventional materials (cf. Marcel Duchamp's readymades) and multiple media; another frequently used method exploited the malleability of language, and this was perhaps inspired by many of the artists being conversant in multiple languages.

A potent international multimedia movement with roots in Zurich's Cabaret Voltaire, Dadaism emerged in reaction to the horrors of the First World War. While its aesthetic far too often gets reduced to formulas like "the world didn't make sense so their art didn't make sense," there are far more complex ideological underpinnings that took issue with nationalism and colonialism, bourgeois politics and aesthetics, and the destructive potential of modern industrialism. That having been said, Dadist ideology was largely centered on shock value and the opportunity for critical rethinking that came with it. One key way they achieved this was through the use of unconventional materials (cf. Marcel Duchamp's readymades) and multiple media; another frequently used method exploited the malleability of language, and this was perhaps inspired by many of the artists being conversant in multiple languages.

We'll start with selections from Jerry Rothenberg and Pierre Joris' Poems for the Millennium, including a brief critical intro and work by Tristan Tzara, Hugo Ball, Marcel Duchamp, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and Kurt Schwitters: [PDF]. Through the materials below, we'll look in greater depth at interpretations of selections from "The Complete Sound-Poems of Hugo Ball"

|

| "Karawane," perhaps Ball's best-known poem. |

First, here's the one and only Marie Osmond(!) discussing Ball on the old Ripley's Believe It or Not television show and reciting "Karawane":

And here's Canadian conceptual poet Christian Bök performing the piece [MP3] along with "Seahorses and Flying Fish" (Seepferdchen und flugfische) [MP3] and "Totenklage"[MP3]. Dutch composer and sound poet Jaap Blonk offers a take on "Seahorses and Flying Fish" here: [MP3] (we'll be encountering more from Bök and Blonk in our next two classes, by the way). Next, here are two takes on "Karawane" by Jerry Rothenberg, one with musical accompaniment by Bertram Turetzky [MP3] and a solo vocal performance here [MP3].

While working on Talking Heads' third album, Fear of Music (1979), David Byrne found himself unable to come up with words for an evocative polyrhythmic track the band pulled together at the end of the sessions. Producer Brian Eno suggested he try singing lines from Ball's poem "Gadji beri bimba" over the track as a way around his writer's block, but rather than simply use them as placeholder lyrics, the band wound up keeping Ball's gibberish, and the finished song, "I Zimbra," was not only given prominent place as the album's opening track, but served as a blueprint for the musical experimentation they'd do on future records like Remain in Light (1980) and Speaking in Tongues (1983). Here's a particularly incendiary version of "I Zimbra" (paired with Byrne's solo track, "Big Business") from the concert film Stop Making Sense ("I Zimbra" begins at 4:52):

For comparison's sake, here are the lyrics to "I Zimbra":

I Zimbra

Gadji beri bimba clandridi

Lauli lonni cadori gadjam

A bim beri glassala glandride

E glassala tuffm I zimbra

Bim blassa galassasa zimbrabim

Blassa glallassasa zimbrabim

A bim beri glassala grandrid

E glassala tuffm I zimbra

Gadji beri bimba glandridi

Lauli lonni cadora gadjam

A bim beri glassasa glandrid

E glassala tuffm I zimbra

As an interesting intertextual complement to these contemporaneous Dada poems and later interpretations, I'd also like you to take a look at a few selections from Rothenberg's 1983 collection, That Dada Strain [PDF]. Audio for certain poems is posted below:

- on That Dada Strain [MP3]

- That Dada Strain [MP3]; with musical accompaniment [MP3]

- A Glass Tube Ecstacy (for Hugo Ball): [MP3]; with musical accompaniment [MP3]

Mamie Smith's "That Dada Strain" (1922), which gives Rothenberg's sequence its title, can he heard below:

Finally, let's consider two more contemporaneous experiments in asemic writing. First, our old friend Charles Bernstein's provocative poem, "Lift-Off" [link, click "next page" for the end of the poem] from 1979's Poetic Justice, which transcribes the contents of the correction (think Wite-Out) ribbon on the poet's typewriter. You can hear Kenny Goldsmith's performance of the poem at a celebration of Bernstein's new and selected poems, All the Whiskey in Heaven, here: [MP3]. Also, here's David Melnick's PCOET [link], a book of 83 deeply fragmented micropoems (feel free to browse as much or as little as you'd like).

Monday, April 13 — Indigenous Poetics via Jerome Rothenberg

On Monday we'll spend an entire class considering the work of Jerome Rothenberg, primarily through his role as a cultural anthropologist and archivist of Native American poetic traditions, but we'll also look at a little of his own poetry inspired by his proximity to the Seneca Nation.

It's impossible to understate Rothenberg's importance as, for all intents and purposes, the inaugurator of the field of Ethnopoetics, through groundbreaking anthologies including Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia and Oceania (1968) and Shaking the Pumpkin: Traditional Poetry of the Indian North Americas (1972) — from which most of our readings today will be drawn — continuing to the brand-new Barbaric Vast and Wild: An Assemblage of Outside and Subterranean Poetry from Origins to Present.

Part of the innovation in Rothenberg's approach is that he treated his subjects with the utmost respect, immersing himself within the cultural traditions under consideration, rather than engaging in cultural tourism. He sought to undertake, as David Noriega observes, "a method of translation that would encompass more than just the poetic content and structure of the songs," including their "intricate and polyphonic arrangement of voices, images, and 'pure' sounds." As he notes on the back cover of Shaking the Pumpkin: "I am not doing this for the sake of curiosity, but I have smoked a pipe to the powers from whom these songs came, and I ask them not to be offended with me for signing these songs which belong to them."

As part of this dedication, Rothenberg moved to the Allegheny Seneca Reservation in 1972, where he studied under Richard Johnny John, "one of the leading singers and makers-of-songs at the Allegany (Seneca) Reservation in western New York State, descended from singers ... very important in their own time." In A Seneca Journal (1978) we see firsthand the influence this experience had upon Rothenberg's own poetry.

As part of this dedication, Rothenberg moved to the Allegheny Seneca Reservation in 1972, where he studied under Richard Johnny John, "one of the leading singers and makers-of-songs at the Allegany (Seneca) Reservation in western New York State, descended from singers ... very important in their own time." In A Seneca Journal (1978) we see firsthand the influence this experience had upon Rothenberg's own poetry.

|

| Three Friendly Warnings (1973), Richard Johnny John, Jerome Rothenberg, Ian Tyson (click to enlarge). |

from A Seneca Journal: [PDF]

more from Shaking the Pumpkin: [PDF]

If you're interested in learning more about Rothenberg's "total translations" of Navajo horse songs, here's an article on the Poetry Foundation's website: [link]. Rothenberg's three-part interview with Richard Johnny John can be found here and here. These last resources are entirely supplemental, and not required for Monday.

Sunday, April 5, 2015

Friday, April 10 — Digital // Interactivity

|

| The user interface for David Jhave Johnston's PennSound MUPS (see below). |

Erica T. Carter / Issue 1

Erica T. Carter was a pseudonym used by Jim Carpenter for work written by his Electronic Text Composition program (ETC), which was created about a decade ago while working as an adjunct at UPenn's Wharton School of Business. This sophisticated writing algorithm, which was available via the web until Carpenter's retirement several years back, allowed users to generate poems with great control over variables like length, syntactical complexity, and so forth. What I recall hearing was that ETC's word bank was drawn from digesting the collected works of Emily Dickinson, however it seems that the poems were generated from a much more diverse array of materials — from canonical authors like Joyce and Hawthorne to daily news articles. I do know that Carpenter successfully published a number of poems in various journals, and Erica was often praised for how well she captured the essence of a modern woman's life. You can browse through ETC's collected works here, which comes complete with a record of source texts, seed words, and other determining factors in the composition of each poem. If you're interested you can also read a more technical description of how ETC works here.

One can't mention ETC without also mentioning the controversy surrounding Issue 1, a 3,785 page collection of poems by practically everyone and anyone in the poetry world, living and dead, published in the fall of 2008. The only problem was that none of these people had actually submitted work — the work attributed to each author was generated by ETC and then assembled into the anthology by (at first) clandestine editors Stephen McLaughlin, Gregory Laynor, and Vladimir Zykov. As Al Filreis notes in a blog post on the episode: "Many poets google themselves, or receive messages called 'Google alerts' whenever their names appear anywhere on the web, and so, in short, they found themselves 'published' in this 'issue.' When they read poems they had not themselves written, some were tickled (gotten by the gotcha) while others were angry." You can get a fuller sense of the reactions by reading Kenneth Goldsmith's Harriet post on Issue 1 and the comments that follow it. As he notes, "either you're in or you're not," and that alone was enough to piss people off. Towards that end, I should add that I felt deeply hurt that I was not "in," until several years later when I realized that the editors had just butchered my last name (Hennesy, instead of Hennessey)(I'm just kidding)(not really . . .). You can browse Issue 1 here.

As a footnote to all of this, while researching the fate of ETC, I spoke briefly with McLaughlin, Carpenter, and Chris Funkhouser (see below) and there's hopes that ETC might soon be resurrected.

Chris Funkhouser

It's hard to categorize Chris simply, because he wears so many hats — poet, scholar, audio archivist, musician, media theorist, one-time webmaster of Amiri Baraka's homepage, and so on — but for today, I'd like to draw your attention to a few projects of his.

First, there's Funk's Sound Box 2012, available in two different interfaces, which catalogues each and every one of the 427 recordings Funkhouser made during 2012. "My initial aspiration," he notes, "was to reduce a hundred hours of material I recorded to something along the lines jukebox-length cuts. That did not happen fully, largely because of the difficulty involved with what of such interesting material to select, along with the belief that chopping it all up into three minute segments seemed unwise." "I also seek to encourage play, and what I have only partially accomplished — and still aspire towards — is creating a sound environment and visual interface that efficiently allows users to mix and match different segments," he continues. "The Stereoeo and Table interfaces do allow users to layer and unify audio segments (about a quarter of which is musical or sonic, without language, noted with a symbol), which can be extremely enjoyable and stimulating."

I also welcome you to look at some of Funkhouser's Flash-based digital poetry pieces, which can be found by scrolling down to the bottom of this page. These pieces, which often showcase a Mac Low-esque etymological fascination by all of the words contained within a word of phrase, make good use of sound, image, text, color, and movement to create ever-changing wordscapes that challenge readers to actively hew their own path through the presented materials. Finally, as a supplemental text (and a wholly optional one) I gladly offer up Funkhouser's 2007 talk on IBM Poetry at the Kelly Writers House, which is segmented thematically with links out to the discussed works.

Brian Kim StefansAs a footnote to all of this, while researching the fate of ETC, I spoke briefly with McLaughlin, Carpenter, and Chris Funkhouser (see below) and there's hopes that ETC might soon be resurrected.

Chris Funkhouser

It's hard to categorize Chris simply, because he wears so many hats — poet, scholar, audio archivist, musician, media theorist, one-time webmaster of Amiri Baraka's homepage, and so on — but for today, I'd like to draw your attention to a few projects of his.

First, there's Funk's Sound Box 2012, available in two different interfaces, which catalogues each and every one of the 427 recordings Funkhouser made during 2012. "My initial aspiration," he notes, "was to reduce a hundred hours of material I recorded to something along the lines jukebox-length cuts. That did not happen fully, largely because of the difficulty involved with what of such interesting material to select, along with the belief that chopping it all up into three minute segments seemed unwise." "I also seek to encourage play, and what I have only partially accomplished — and still aspire towards — is creating a sound environment and visual interface that efficiently allows users to mix and match different segments," he continues. "The Stereoeo and Table interfaces do allow users to layer and unify audio segments (about a quarter of which is musical or sonic, without language, noted with a symbol), which can be extremely enjoyable and stimulating."

|

| A screenshot from Aleatory Constellation (2007). |

Stefans appears here for two different reasons: first, I'd like you to look at some of the examples discussed in his 2008 Kelly Writers House talk on "Language as Gameplay" — including the Flash setting of the E chapter of Christian Bök's Eunoia (which we'll be looking at shortly), Jason Nelson's Literary Textual Games (n.b. you will be haunted by the phrase "come on and meet your maker" after playing), and Judd Morrisey's "The Jew's Daughter" — and listen to his comments on each.

| A screencap from Stefans' Suicide in an Airplane 1919. |

Then listen to his comments on his own work and interact with some of those pieces (don't worry about the expired security certificate — it's safe to proceed). Another wonderful piece by Stefans not available on the aforelinked UbuWeb page is his "Suicide in an Airplane 1919," which you can view here.

Finally, I'd like you play around with David Jhave Johnston's PennSound MUPS, a mash-up engine that uses pre-selected tracks from the PennSound archives, allowing for some interesting textual (and textural) interactions. Here's Al Filreis' initial write-up of the project on Jacket2, which also includes comments from Charles Bernstein, Johnston, and yours truly:

Working with our PennSound audio files, Jhave Johnston has created a prototype mashup machine that enables on overlay of poets' sounds, with an option to turn on WEAVE, which senses silence (e.g. between lines or stanzas in a performance) and automatically intercuts from one short file segment to another, creating a flow of shifting voices. "I always figured," says Charles Bernstein, my co-director at PennSound, "that once we had a substantial archive of sound files, the next phase would be for people to use them in novel ways." "Reminds me," says Michael S. Hennessey, PennSound's editor, "of one of my favorite things to do with the site before we switched to the current streaming codec, which doesn't allow for simultaneous play: pull up a few author pages — best of all Christian Bök — and start layering tracks over his cyborg opera beatboxing." Jhave adds: "My motivation for building it is similar to Michael's: a joy in listening to things overlap."

You can interact with PennSound MUPS here.

Friday, April 3, 2015

Your Mac Low and Ashbery Performances

While I've posted these to our Facebook group, I thought I'd also share the recordings of your performances of the Mac Low and Ashbery pieces here:

Wednesday, April 1, 2015

Wednesday, April 8 — Poets Theater

We'll wrap up our subsection on poetry and performance by spending a class on a fascinating, if somewhat undefined genre: poets theater. In one conception, it's simply dramatic, happening-like events written by authors who predominately work in the poetic mindset. To others, the genre has certain aesthetic baggage, including simplicity in staging and props, low or non-existent budgets, embracing its amateur nature, and a certain spontaneity and occasional-ness. Several poets involved in poets theater discuss these distinctions in "What Is Poets Theater?," a piece organized by Thom Donovan on the Poetry Foundation's blog, Harriet.

Given the great enjoyment we've all had collaboratively performing texts by Mac Low and Wiener over the last few classes — and the fact that CCM drama majors make up approximately 1/3 of our class — I think this should be a lot of fun.

Given the great enjoyment we've all had collaboratively performing texts by Mac Low and Wiener over the last few classes — and the fact that CCM drama majors make up approximately 1/3 of our class — I think this should be a lot of fun.

We'll take a look at five very short plays taken from the excellent Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater 1945–1985, edited by Kevin Killian and David Brazil: [PDF]

- Lew Welch, "Abner Won't Be Home For Dinner" (1966)

- Joe Brainard, "The Gay Way" (1972)

- Rosmarie Waldrop, "Remember Gasoline?" (1975)

- Ted Greenwald, "The Coast" (1978)

- Leslie Scalapino, "leg, a play" (1985)

As well as a handful of microdramas taken from Kenneth Koch's 1988 volume, 1000 Avant Garde Plays [PDF]. You can watch a brief video of selections from a somewhat precious staging of Koch's plays below (warning: it's really cheesy):

Monday, March 30, 2015

How I Made a Podcast

Last year, I was tasked with a weekend project not unlike the audio documents you'll be making as part of your finals: put together an "audio essay" to be shared as part of PennSound's 10th anniversary celebration. The resulting piece, the product of maybe 6–8 hours' work, ran just over nine and a half minutes, and you can listen to it below:

I thought I'd share some notes on my process with the hopes that it might be helpful for you as you get started on your finals.

1. Outline your basic concept

I wanted my piece to generally break down into two basic sections: first, a short discussion of how I came to work at PennSound and some of the notable discoveries I made during my early years there, and second, discussion of a few memorable sessions I'd recorded with a few favorite poets.

2. Gather and prep raw materials

1. Outline your basic concept

I wanted my piece to generally break down into two basic sections: first, a short discussion of how I came to work at PennSound and some of the notable discoveries I made during my early years there, and second, discussion of a few memorable sessions I'd recorded with a few favorite poets.

2. Gather and prep raw materials

I decided upon the recordings that I wanted to use for my piece and downloaded them from PennSound, then used Audacity to make the smaller cuts I'd be using. Note that I've used simplified yet descriptive file names for the cuts I've made, distinguishing the order I want to use them in, or just their contents.

For the section mimicking several Christian Bök tracks playing simultaneously, I made a sub-mix to export as its own MP3 file. The blue shape under the last track is contouring its volume level to create a fade-in. Thought it's not easy to see, I've also stereo-panned the two beatboxing tracks relatively hard left and right, while the "lead vocal" goes closer to the middle.

|

Here, while trimming down a short snippet from the Ashbery/Lauterbach "Litany," you can see that I've left room tone (i.e. "silence;" the noise floor of tape hiss) on either side, so that I can seamlessly integrate it with my own voice-over when stitching the track together.

|

3. Prepare your script

It's much easier to record your voice-over when you're reading from a pre-prepared script, so take the time to write things down in advance, and mark out where your insertions will go as well (as you can see below). Even though you're free to improvise when recording, it'll help you work around tricky diction if you have clear reading copy to work from.

4. Record and edit your voice-over

For my piece, I used my little Tascam portable on a tripod right in front of my laptop, then copied the file to my computer so I could edit it in Audacity. My preferred method is to record everything linearly in one long take, then go through and pull out the individual files as needed. You're bound to make mistakes, and when you do, just leave a sufficient pause and then start again. It's also not a bad idea to give a second take when in the moment you feel less than enamoured of a certain reading. Try to record sections of voice-over in as continuous sections as you can, but leave sufficient pauses between sections so you can trim down, and/or make splices with enough room tone to cover the gaps.

Here, you can see that I've cut a section of voice-over very closely at the head, to eliminate the sound of me inhaling before I start speaking, but left a silent tail that I can use to overlay another voice-over section.

Organize your voice-over sections in a similar fashion as your samples: I've numbered them in order of their appearance (n.b. two pieces that have alternate takes) and added a few words to clue me in to their contents.

5. Final construction

I opted to use Garageband, since that's the software I'm most comfortable using, to lay out my final podcast. Here's what the full piece looks like in the editor:

You'll notice I've used two tracks for voice-over and two tracks for the inserted samples (which are ducked, i.e. the software will always make the voice-over tracks louder than the samples), plus one track for music (I eventually ended up ditching the backing music). I use two tracks for each section so that I can put together tighter edits using that room tone before and after the sound snippets without cutting any one track short (i.e. those sounds overlap on adjacent tracks so they can play out through the edit point). Edits often need to be fine-tuned by moving a sample back and forth little by little, sometimes just a fraction of a second to get the right pacing, the right pauses, and natural speech-like flow. You can also use fade-ins and fade-outs to make pieces fit together more smoothly.

Here, you can more clearly see the interplay of tracks on a section from the middle of the piece. The second and third tracks are my own voice-over, while the fourth and fifth are samples of other poets. Originally the last track was just for samples that needed fade-ins (namely the Tardos) but I wound up doing a fade-in on the Bök as well.

It certainly takes a lot of trial and error — and by no means would I call myself an expert — but I hope that this might be of use to you as you start thinking about your final projects.

5. Final construction

I opted to use Garageband, since that's the software I'm most comfortable using, to lay out my final podcast. Here's what the full piece looks like in the editor:

You'll notice I've used two tracks for voice-over and two tracks for the inserted samples (which are ducked, i.e. the software will always make the voice-over tracks louder than the samples), plus one track for music (I eventually ended up ditching the backing music). I use two tracks for each section so that I can put together tighter edits using that room tone before and after the sound snippets without cutting any one track short (i.e. those sounds overlap on adjacent tracks so they can play out through the edit point). Edits often need to be fine-tuned by moving a sample back and forth little by little, sometimes just a fraction of a second to get the right pacing, the right pauses, and natural speech-like flow. You can also use fade-ins and fade-outs to make pieces fit together more smoothly.

Here, you can more clearly see the interplay of tracks on a section from the middle of the piece. The second and third tracks are my own voice-over, while the fourth and fifth are samples of other poets. Originally the last track was just for samples that needed fade-ins (namely the Tardos) but I wound up doing a fade-in on the Bök as well.

It certainly takes a lot of trial and error — and by no means would I call myself an expert — but I hope that this might be of use to you as you start thinking about your final projects.

Final Project Guidelines (Due Thursday, April 30th)

Scope and Components

The concept behind your final project is relatively simple: you'll choose one idea/technique/author that we've covered during the semester and undertake a more in-depth critical investigation, which will have both a written and audio component. In terms of the scope this might take several forms:

The concept behind your final project is relatively simple: you'll choose one idea/technique/author that we've covered during the semester and undertake a more in-depth critical investigation, which will have both a written and audio component. In terms of the scope this might take several forms:

- You might choose to do deeper reading/listening within the assigned texts for a given topic (i.e. including the assigned work that we did cover as well as those texts we didn't).

- You might choose to do deeper reading/listening outside of the assigned texts for a given topic (i.e. read more widely within a certain assigned author's work and/or find other authors to include in your analysis).

- You might choose to make ideological/aesthetic/technique-based connections between authors/topics — ideally ones not explicitly made during our class discussions — working within or outside of the assigned readings.

The key point here that you don't want to lose is that you'll be making an argument, taking a stand, tracing aesthetic threads and/or lineages (i.e. the development of ideas), and not just compiling a greatest hits list, or rehashing points that we've made as a class, or that I've made through the organization of the class. Likewise, in terms of outside readings, I can make suggestions but also welcome you to do your own research on the topic(s) of your choosing.

As for the audio component of the final, it might also take several forms:

- It will very likely be something following the podcast model, establishing a dialogue, of sorts, between your recorded voice-over and samples of recordings by poets themselves (taken from archives like PennSound, the Elliston Project, UbuWeb, etc.) or of you reading their work (if recordings don't exist). In essence, this would be more like a distilled version of your paper that's augmented by actual recordings of the poets.

- It could be an audio artifact that critically demonstrates some key point from your essay, which is then set up by the essay itself, however it's important to be mindful of the fact that this shouldn't be a creative endeavor like the midterm sound collages. If you want to pursue this route, we should discuss your plans before I greenlight your project.

- It could be a largely textual endeavor in which micro-edits of recorded audio are embedded throughout, serving the same function as, and accompanying, quotations. A fine example of this possibility can be found here, in Bob Perelman's "A Williams Soundscript," an analysis of William Carlos Williams' "The Sea-Elephant." Again, we'll need to discuss your plans in advance to make sure you're on the right track.

As for podcast models, there are a great many to follow as inspiration, including PoemTalk, Al Filreis' PennSound Podcasts, Charles Bernstein's Close Listening, This American Life, Garrison Keillor's the Writers Almanac, and several from the Poetry Foundation: Poetry Off the Shelf, Essential American Poets, and Kenny Goldsmith's Avant-Garde All the Time, among others. Ideally, you'll want to aim for something more finely interwoven and dialogic than the DJ model — i.e. you talk for a little bit and then play an entire recording.

Facts and Figures (i.e. deadlines, page count, formatting, etc.)

Facts and Figures (i.e. deadlines, page count, formatting, etc.)

I want you to do your best work without feeling constrained, but at the same time I don't want to set minimum length requirements that are impossible for the average student to reach. Therefore, I'm setting minimums that I expect many of you will greatly exceed, and I welcome you to do so. Your written essay should be at least six (6) full pages long (and by six pages, I mean that the text of your essay itself makes it to the very bottom of the the page, or better yet onto a seventh), and written in MLA style (including a proper header, parenthetical in-text citations and a works cited list, which doesn't count towards your page count, at the end), double-spaced in 12-point Times New Roman, no tricked-out margins, etc. Your audio component should me a minimum of three minutes, though I could very easily see students producing pieces five, ten, even fifteen minutes long.

While six pages seems like an endlessly long paper, I can assure you that it's not really a lot of space to discuss these topics in great depth, therefore I wholeheartedly encourage you to dispense with any and all filler, including bloated rhetoric and lengthy five-paragraph-style introductions that ultimately say very little while taking up a lot of word count. Don't hover over the surface of the issues — dive right in and get to the heart of your argument from the start. I also recommend that unless you have compelling reasons to do otherwise, organize your essay around the topics (characters/techniques/etc.) you've chosen to discuss, rather than proceeding chronologically or dealing with each author individually, and also that you write through the source texts themselves, as demonstrated in the "Making Effective Arguments" post I put up at the start of the term. Finally, make sure that you are following the conventions of MLA formatting (which can be found in numerous places on the internet; a link with guidelines can be found on the right-hand sidebar as well).

You'll e-mail your papers to me (at hennessey [dot] michael [@t] gmail [dot] com) no later than 7:00 PM on Thursday, April 30th. Please include a link to your audio piece on Soundcloud in that e-mail and feel free to share it with our class Facebook group (also, please enable downloads on SoundCloud so I can archive a copy). Because e-mail is an imperfect delivery medium and the UC system is prone to collapse, take note that I'll reply to each paper received, letting students know that it's arrived safely, so if you don't receive that e-mail, get in touch with me, and should you have any questions or concerns prior to the deadline, don't hesitate to drop me a line.

Also, please don't forget that tardy projects will be docked a full letter grade for every day they're late and that papers that are less than the stated limit of six full pages will automatically receive an F.

Class Feedback

Finally, because I consider this course an organic and malleable construct, I'd greatly appreciate it if you took the time to answer these questions in a separate document. Please don't feel the need to flatter me or the course materials either — I respect your honest opinions about the class and what did or didn't appeal to you.

- What 10 authors/class topics were most useful/interesting to you?

- What 5 authors/class topics were least useful/interesting?

- Are there any authors/topics you wish we had covered that we didn't?

- Are there any activities (i.e. audio work) that you'd have liked to do? (Or, should the class involve more audio work?)

- Are there any authors you're eager to investigate further after the term is over?

Wednesday, March 25, 2015

Monday, April 6 — Performance Scores: Brecht, Ono, Grenier, Brautigan

|

| George Brecht performs "Incidental Music" in 1961. |

We've read Susan Sontag's thoughts on the (then-)burgeoning artform known as "happenings," have seen some pieces from Jackson Mac Low and Hannah Weiner that embody their spirit, and have acquainted ourselves with the aesthetic philosophies of one of their major influences, John Cage. Today, we'll spend some time looking at a selection of pieces from George Brecht and Yoko Ono, two key members of the Fluxus movement, an international Neo-Dadaist collective that came to prominence in the 1960s.

|

| Two event scores by George Brecht. |

First, the master of the event score, George Brecht, whose ambitious hybrid pieces found connections between poetry, music, choreography, and drama, and frequently demonstrated a subversive sense of humor. You can read through a collection of many of Brecht's pieces here, and even see variations between different performances in different years.

Next, we'll read selections from Yoko Ono's iconic book Grapefruit. First published in 1964, the book received more mainstream attention after a 1970 edition featuring an introduction by Ono's husband, John Lennon — "Hi! My name is John Lennon. I'd like you to meet Yoko Ono..." — and the surrealistic performance instructions contained therein fit nicely with the couple's "bagism" ethos, and even, in a way, the rhetoric behind their "War is Over! (if you want it)" billboard campaign.

Next, we'll read selections from Yoko Ono's iconic book Grapefruit. First published in 1964, the book received more mainstream attention after a 1970 edition featuring an introduction by Ono's husband, John Lennon — "Hi! My name is John Lennon. I'd like you to meet Yoko Ono..." — and the surrealistic performance instructions contained therein fit nicely with the couple's "bagism" ethos, and even, in a way, the rhetoric behind their "War is Over! (if you want it)" billboard campaign.In Grapefruit, Ono creates hybrid aesthetic constructs similar to Brecht's, with performance scores that create paintings, films, music, and personal meditative acts. You can read selections from Grapefruit here: [PDF]. Acorn, a sequel of sorts to Grapefruit, was published in 2013; you can read a few excerpts from it here.

Next, we'll shift gears a little bit, to look at two imaginative texts that demand an interactive performance from their readers. First, Robert Grenier's Sentences (1978), originally produced as a boxed version of 500 individual cards, which can be read in any order. You can browse a virtual version of the text, which will randomly and reductively select cards from the deck until all options are exhausted, here (read as much or as little as you'd like). Photos of the original version can be found here.

|

| Cards from Grenier's Sentences on display in a gallery in Brooklyn, May 2013. |

Another iconic conceptual poetic text which demands a sort of performance from its readers is Richard Brautigan's Please Plant This Book, first published in the spring of 1968 as a folder containing eight seed packets, each with a poem printed on the outside. Like the Grenier, it's been lovingly resurrected in a virtual version here, however the seeds aren't included. Nonetheless, try to imagine the experience of the original, whereby the reader completes the act of reading each poem by planting the seeds, and thereafter the poem continues, in a sense, as the plant, flower, or vegetable that comes forth. In "Lettuce," Brautigan muses that "The only hope we have is our / children and the seeds we give them / and the gardens we plan together," and that figurative wisdom becomes literal with a strange and wonderful hybrid text like Please Plant This Book.

Friday, April 3 — Polyvocality: Ashbery/Lauterbach, Howe/Grubbs, Bernstein, the Velvet Underground

Today we'll continue an aesthetic thread that, for us, began with some of the later John Giorno poems we looked at and then carries on through Jackson Mac Low and Hannah Weiner — namely, texts that, either through their presentation on the page or their realization in performance, stress a polyvocal approach to poetry, with multiple voices that complement or even compete with one another.

|

| Ann Lauterbach (left) and John Ashbery (right). |

First up, we have a 1980 recording of the first section of John Ashbery's "Litany" (first published in 1979's As We Know), which famously provides readers with these instructions: "The two columns of 'Litany' are meant to be read as simultaneous but independent monologues." Of course such things are impossible for a solitary reader, but when reimagined as a stereo multitrack version (with Ashbery reading the left column and poet Ann Lauterbach the right), we finally hear the poem as it was intended to be received, though at the same time suddenly lose access to much its semantic content as we try to pay attention to the two voices at once. Ironically, in several readings around the time of its release, Ashbery offered less proscriptive takes on how the poem could be performed, and he himself tended to either jump from column to column as he saw fit, or to read the left and right pages sequentially. "Litany," Part One [PDF, MP3]

|

| Susan Howe and David Grubbs. |

Next, we'll look at two tracks from Thiefth, a 2005 CD release by poet Susan Howe and multi-instrumentalist David Grubbs, which features complex performances of two of Howe's historical investigations — "Thorow" [PDF] and "Melville's Marginalia" [excerpt: PDF] — with musical accompaniment and voice manipulation (via the MAX/MSP software). The album's liner notes provide more background on the collaboration:

Thiefth is the first collaboration between poet Susan Howe and musician and composer David Grubbs. The two were brought together when the Fondation Cartier proposed a collaborative performance. Grubbs had been an ardent reader of Howe's for more than a decade, and the opportunity to work with Howe's poetry and her voice immediately intrigued. In late 2003, the two set about to create performance versions of "Thorow" and "Melville's Marginalia," two of Howe's longer poems.

Drawing from the journals of Sir William Johnson and Henry David Thoreau, "Thorow" both evokes the winter landscape that surrounds Lake George in upstate New York, and explores collisions and collusions of historical violence and national identity. "Thorow" is an act of second seeing in which Howe and Grubbs engage the lake's glittering, ice surface as well as the insistent voices that haunt an unseen world underneath.

"Melville's Marginalia" is an approach to an elusive and allusive mind through Herman Melville's own reading and the notations he made in some of the books he owned and loved. The collaging and mirror-imaging of words and sounds are concretions of verbal static, visual mediations on what can and cannot be said.

You'll find PDFs of the texts at the links above, and you can listen to the album's individual tracks (along with several later collaborations including "Souls of the Labadie Tract" and "Frolic Architecture") on PennSound's Howe/Grubbs author page.

|

| Charles and Emma Bee Bernstein |

We'll also visit again briefly with Charles Bernstein, taking a look at a pair of pieces from diverse periods in his career. First, listen to "Piffle (Breathing)" [MP3] — another track from Class (you've already listened to "Class," "My/My/My," and "Goodnight"), which was recorded with Greg Ball and Susan Bee Bernstein in 1976. Then we'll jump forward to the 2003 poem "War Stories" and a two-voice rendition of it performed with the poet's daughter, Emma [poem and MP3 here]

|

| The Velvet Underground in 1969 around the release of their third album: (left to right) Doug Yule, Lou Reed, Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker. |

Finally, we've already talked a little bit about the Velvet Underground's Lou Reed recently, taking a look at some of his more narrative songs, but today I'd like to take a look at one of that band's more infamous tracks, "The Murder Mystery" (taken from their self-titled 1969 album). This nine-minute track exploited the stereo medium with Reed and guitarist Sterling Morrison reading separate competing lyrics in the left and right channels during the verses, with drummer Maureen Tucker and bass/keyboard player Doug Yule trading off overlapping vocals on the choruses. Reed would later publish a version of the lyrics in The Paris Review in 1972, but this version comes from his collected lyrics, Between Thought and Expression: [PDF]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)