|

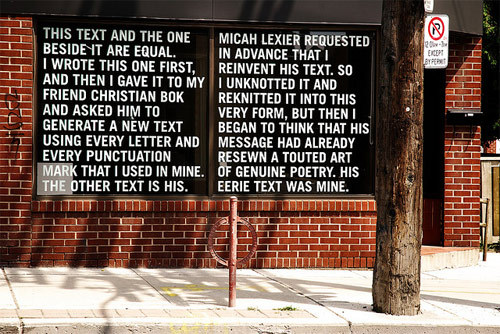

| Christian Bök's "Two Equal Texts," on-site installation. |

First up is Christian Bök, who's perhaps best known for his book-length Oulipian experiment, Eunoia, a lipogramatic text, that is one in which some sort of linguistic restriction guides its composition: specifically, each of the five chapters, named for one of the vowels, only contains words containing those vowels. In addition, Bök has instituted several other rules, including making use of at least 98% of all existing words featuring the given vowel, as well as specific tasks, including writing about the act of writing, a feast, a debauch, a nautical journey, etc. You might recall Stefans talking about the text in relation to his setting of the E chapter in last Friday's readings.

We'll look at two chapters in their entirety, and then a few selections from the companion "Oiseau" section, including several variations on Arthur Rimbaud's "Voyelles," which synesthetically ascribes colors to each of the vowels. [PDF] Recordings from Bök's PennSound author page are linked when available.

- Eunoia, chapter A [MP3]

- Eunoia, chapter O [MP3]

- Voyelles [MP3]

- Vowels [MP3]

- Phonemes [MP3]

- Veils

- Vocables [MP3]

- AEIOU

- And Sometimes [MP3]

- Vowels [MP3]

- H (for bpNichol)

- Voile [MP3]

Next, we have bpNichol, shown above with his poem, "The Complete Works." We'll take a look at some selections from The Alphabet Game: a bpNichol Reader, which highlight some of nichol's more purely sonic experimentations, however he worked in a wide variety of media, starting as a concrete poet (a genre that often indirectly features some sort of sonic subterfuge), but moving on to work in collages, musical theatre, television (among other jobs, he wrote scripts and songs for Fraggle Rock) and even very early experiments in computer poetry with First Screening: Computer Poems (1983–84) for the Apple IIe (you can watch an emulated version here). Sadly, nichol died at the very young age of 43 after complications from surgery on his back but his work and influence carry on, most notably in bpNichol Lane (see below) in Toronto, where, at #80, you can find Coach House Press, one of Canada's longest and most-acclaimed publishers of experimental poetry. nichol's PennSound author page can be found here, and your readings are here: [PDF]

In addition to his own writing, nichol founded The Four Horsemen with poets Steve McCaffery, Paul Dutton, and Rafael Barreto-Rivera. This group, which took the ideas of concrete and sound poetry into fascinating — if sometimes perplexing — live performances that combined high-minded literary conceptualism with the raucous energy of a rock show. You can see their performance from Ron Mann's film, Poetry in Motion below, and find a wide variety of recordings on their PennSound author page. For an optional, yet highly-intriguing sonic experience, you might also want to check out Paul Dutton's "so'nets."

Finally, we'll look a a suite of poems published in Poetry Magazine in a special 2009 issue devoted to Flarf and Conceptual poetry which was edited by Kenneth Goldsmith. In his introduction, he makes some (understandably) controversial statements that nonetheless aptly give a sense of the state of contemporary cutting-edge poetic practice:

Start making sense. Disjunction is dead. The fragment, which ruled poetry for the past one hundred years, has left the building. Subjectivity, emotion, the body, and desire, as expressed in whole units of plain English with normative syntax, has returned. But not in ways you would imagine. This new poetry wears its sincerity on its sleeve . . . yet no one means a word of it. Come to think of it, no one’s really written a word of it. It’s been grabbed, cut, pasted, processed, machined, honed, flattened, repurposed, regurgitated, and reframed from the great mass of free-floating language out there just begging to be turned into poetry. Why atomize, shatter, and splay language into nonsensical shards when you can hoard, store, mold, squeeze, shovel, soil, scrub, package, and cram the stuff into towers of words and castles of language with a stroke of the keyboard? And what fun to wreck it: knock it down, hit delete, and start all over again. There’s a sense of gluttony, of joy, and of fun. Like kids at a touch table, we’re delighted to feel language again, to roll in it, to get our hands dirty. With so much available language, does anyone really need to write more? Instead, let’s just process what exists. Language as matter; language as material. How much did you say that paragraph weighed?

As no better (and more appropriate) a source than the Wikipedia page on Flarf observes, "Its first practitioners, working in loose collaboration on an email listserv, used an approach that rejected conventional standards of quality and explored subject matter and tonality not typically considered appropriate for poetry. One of their central methods, invented by Drew Gardner, was to mine the Internet with odd search terms then distill the results into often hilarious and sometimes disturbing poems, plays and other texts."

In particular, I'd like you to take a look at the contributions — which can be found here — from Jordan Davis, Sharon Mesmer, K. Silem Mohammad, Drew Gardner, Nada Gordon, and Gary Sullivan. Aside from Bök, you'll also note the issue contains work by Caroline Bergvall, who we'll be reading next week.

No comments:

Post a Comment